Freud’s iceberg model of the psyche

Our human identity is both static and dynamic. To awaken the person and human me is to become conscious of the subjectivity of our personal, human self. However, even if our human subjectivity is awakened, we may still lag behind on the level of its functioning. This article and, “Knowledge of the Person – the Key Ingredient to Human Transformation”, are intertwined and have been written to address this issue. If we do not know how we function on the human level, meaning we do not have insight into all the components that are at the root of our human functioning, we remain ignorant of ourselves on the level of our psychological self. Our personality is indeed relative and bound by many conditional elements, making it difficult to decipher. However, gradually we will unravel its layers and dimensions to create an intricate and realistic picture.

Such attempts have been made in past spiritual traditions. In Buddhism, for instance, they created the concept of the ‘five skandhas’ through which they attempted to conceptualize the elements constituting our mental and physical existence. The five skandhas (a word which in Sanskrit means ‘aggregates’) are: (1) matter, or body (rupa), the manifest form of the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water; (2) sensations, or feelings (vedanā); (3) perceptions of sense objects (saṃjñā); (4) mental formations (saṃskāras); and (5) awareness, or consciousness, of the other three mental aggregates (vijñāna). Based on this, the wider Buddhist vision is that all individuals are subject to constant change, as these elements of consciousness are never the same. A person can therefore be compared to a river: it retains a certain coherent identity, but the drops of water that constitute it are constantly changing from one moment to the next.

What is important to see about this understanding is that it was based on the underlying assumption that ego and personal self are false; in other words, our personal self was seen as a kind of illusion created by the play of these five elements. Is our personality an illusion? It is only an illusion to those who do not know themselves. The idea behind the concept of the five skandhas was to ‘prove’ the non-existence of ego, but who was coming to this conclusion? It was the ego itself. The relative personal dimension of our soul is not an illusion – it is more relative, but it is still very important. To assume that it is false is pure ignorance; a kind of Buddhist intellectual hogwash. In these two articles, we want to address the reality of the relative. Once we do, once we open up and embrace it as an indivisible part of our true self, we can only then aspire in a true way towards its transformation and alignment with our higher self.

So the main point here is that the relative is, in fact, real, firstly because it serves as the counterpart to the unconditional, and additionally because it has other, further purposes in the life of the soul. The Buddhist concept that ego is just a mirage, is itself a mirage. We have been brainwashed and damaged by the philosophy of non-duality and self-hatred for far too long. No one has ever challenged these concepts because the vast majority of spiritual teachers and scholars are ignorant. Any concepts that are based on the negation of the personal self need to go where they belong – into the garbage bin. Without knowing our psyche and the dimension of the person, we have no chance of truly understanding and transforming the personal dimension of our very own self. We will live in an existential split between the unconditional dimension of our soul and our divine, personal consciousness.

In the end, you will be astonished to discover that it is the personal within you that truly your highest self.

Creating a Provisional Map of the Psyche

Our psychological self is a multilayered, living organism composed of many interconnected dimensions. First of all, we need to make a clear distinction between the person and personality. Personality, which is the outermost layer of the soul, represents our psychological dimension, comprised of thoughts and emotions that revolve around three, main centers – emotional me, feeling me and subconscious me, which is the center of the subconscious mind. Personality is normally not conscious of its own subjectivity but, when one has evolved sufficiently, it does become linked to consciousness. The person, on the other hand, is our multifaceted personal center of intelligence. It is the thinker, decision maker, discriminator, and it is also the center of personality.

In creating a map of the psyche, we must first of all define what we mean by this term. The root of the word ‘psyche’ is actually ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’. However, its meaning obviously changed and evolved through specific types of usage. For our purposes, we take the term ‘psyche’ to signify to the core psychological dimension of the soul, which is the product of an intricate and ongoing relationship between the person and the subconscious mind. Both the person and subconscious me are centers of intelligence which are also linked to our emotions and higher feelings.

Unlike the map of the human – which refers to different centers of our personal identity, such as human me, the person, and subconscious me – the map of the psyche aims at defining the different elements that make up our psychological existence. Because much still remains to be discovered, the description below can be approached as a provisional map. Getting in touch with our psychological existence is beyond just getting to know our psychological tendencies, as it requires unraveling the different layers of the psyche that dwell in the identity of the person.

The human psyche can be roughly divided into two compartments, the person and the subconscious mind, the latter of which is also connected to the emotional centers. The person, however, also has his own subconscious dimension independent of the subconscious mind. In turn, the subconscious of the person also has links to the emotional centers.

The Subconscious Mind

The subconscious mind serves as a rudimentary base of the psyche, and before the person develops, our existence is entirely based on it. This is the pre-person (or pre-egoic) stage of evolution of the psyche.

The subconscious mind is composed of two spheres – the unlearned collective and the personal. The unlearned collective part includes the instinctive and autonomic drives of the psyche, autonomic in the sense that they are involuntary or unconscious. In the initial stages of evolution, the collective part of the subconscious mind is more dominant than the personal. For instance, if a bee stings us and dies to protect the beehive, it is not making a personal choice. Its choice is collective; the bee does not choose to die but is instinctively serving the higher good and survival of the beehive. In a similar way, a human baby cries when it is hungry or in pain because it instinctively seeks survival.

The personal dimension of the subconscious mind develops in the context of its personal history, meaning what it has acquired or learned subconsciously through exposure and experience. In turn, this is also linked to its desire to survive and to pursue its basic instinct to seek gratification and receive pleasure in any form, be it physical or emotional. Even though humans are still very much entrenched in the collective subconscious, their personal subconscious is much more developed than that of other creatures.

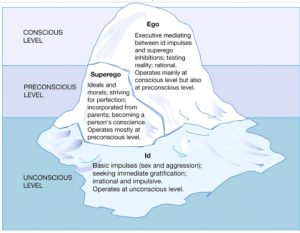

The basic layers of the subconscious mind resemble what Freud called the ‘id’, which are the drives and impulses which move us seek comfort, pleasure, and immediate satisfaction. These instinctive drives and impulses are, of course, not exclusive to humans. However, they are more developed in humans, especially because they are guided by the personal subconscious mind, which is a storehouse of our individual life experiences, memories, and acquired tendencies based on the feedback we have had from processing our countless past responses to the general input from the external world.

The Subconscious of the Person

Interestingly, even though Freud addressed the pre-conscious and unconscious layers of the person (the person being ‘ego’ in his terminology), his model lacks any clear distinction between the subconscious mind and the subconscious dimension of the person.

The subconscious of the person is not the subconscious mind itself but rather what has been unconsciously integrated from personality as a whole into the person. The subconscious mind is what arises mentally and emotionally in our personality prior to us making any conscious choices, while the subconscious of the person is a combination of the unpremeditated, pre-conscious base from which we respond to what is manifesting in the subconscious mind, plus how we feel as the person before anything from the subconscious mind comes to the surface of our subconscious or conscious recognition.

The person is the most conscious part of the psyche, even in the case of people who are completely unconscious. They can be unconscious in three ways – in how they respond to the subconscious mind, in their relationship with the subconscious in the person, and in their relationship with the actual identity or subjectivity of their person. Still, even those who are very unconscious do, in their own way, relate unconsciously to both the subconscious mind and to how they subconsciously feel as the person. This means that even they can be relatively conscious on the level of the function of the person, while remaining unconscious in his identity.

For example, a person can be depressed, which is common in our society. He feels depressed, suffers, and tries to deal with it by either repressing the feeling, denying it, taking anti-depressants, or seeking some kind of more constructive solution. But he does not have access to the root of it, because this feeling of depression is so deep and incomprehensible. A person in this situation is commonly torn between the negative or disturbing subconscious mind and disturbed layers in the subconscious of his own person. The relatively conscious part of the person is trying to cope with it, but is compensating in all kind of ways, through various distractions, displacements, or false acceptance. In truth, without spiritual awakening, there is simply no solution, and he is left to suffer and do what he can to suppress the symptoms.

The Evolution of the Person

But let’s take a few steps back and look at how the person develops. When we are born, we immediately begin to struggle, because there is by nature a battle to survive physically and to receive love in our world. There is an undeniable conflict in everyone’s life between what they want and what they receive. Everyone is frustrated in one way or another, but we keep repressing this frustration, pushing it back into the dark, hidden parts of the psyche. Hence, as we become more adult, the common tendency is to blame our past, our parents, or just our bad luck, for being unhappy.

Everyone is unhappy, except those whose consciousness is so primitive that they cannot even register their misery; in their completely unconscious state they might even think that they are ‘happy’. In fact, such so-called ‘happy’ people have not yet truly become human, because they have failed to get in touch with the basic suffering of human existence. Of course, the deeper reason that people are unhappy is because they are so spiritually hollow and existentially dead that nothing in the world can fill the hole in their being.

Superego

The suffering, frustration, insecurity, fear, and constant struggle fundamental to human life create the foundation for the development of the subconscious of the person. In addition, there are the normalizing, moralizing forces of the collective mind. Even though we are less collective than bees, our very existence is based on living in and fitting into society and, in order to be part of it, we have to learn how to play by the rules or we will be rejected. Social mores are initially imposed by our parents and then later at school, at the workplace, through friends, romantic partners, and so forth, and on the macro level via the larger community and ultimately, the whole human world. So, we are learning how to play by the rules from our childhood, which is when our basic social training begins. We are being trained by social morality, religion, cultural principles (that vary in different societies) and various political games that are indivisible from how society works and which, when combined together, determine our sense of right and wrong. And, while this social education (or brainwashing, when it is not aligned with truth) serves its purpose in helping us acquire a basic sense of conscience and social skills, it also damages us on many levels.

These moral influences combined are what Freud called ‘superego’. Superego is the principle of idealism acquired from our parents and society which causes us to behave, think and feel in a certain way, even if it is against what feels right to us in the moment. Superego has been imposed on us through two main tools: reward and punishment. If we do not behave in the way that is expected of us, we will be punished. If we do behave properly (including conforming in how we feel and think) we will be rewarded, praised, and loved.

The idealistic notions of superego ultimately come to be internalized by each individual, meaning we stop needing parents, teachers, or priests to punish or praise us – we do it to ourselves. We feel proud when we behave according to ‘our’ ideals, and we hate ourselves when we cannot follow them. The superego has unknowingly become infused into the subconscious of the person. What we think and feel is no longer ours, it has been superimposed on the subconscious of the person, and the subconscious and conscious mind then end up trying desperately to deal with all the ensuing contradictions between how one ‘ought’ to feel and behave versus what one naturally feels.

For instance, a husband no longer feels attraction to his wife, despite having made a commitment to be faithful to her, and he feels guilty about it. The underlying morality and judgmentalism are imprinted in society, and thereby in the husband’s personal subconscious. He may, for various reasons, violate the commitment he made, but he will feel sinful and guilty because of not having upheld his superego’s ‘higher’ values.

In another scenario, a man is enlisted into the military to fight ‘bad’ people in a foreign country (as, for instance, happened to the Americans during the Vietnam war). He goes to fulfill his superego’s patriotic ideas, even though he is no more than a pawn, being manipulated by his government and those who are profiting from that violence. If he refuses, he is deemed a coward and feels ashamed. If he fights in such a senseless conflict, he feels like he is fulfilling his duty even though he may either die or be damaged physically and emotionally for life.

Of course, the expressions of superego differ from one culture to another, and some of those expressions are even more at odds with truth than others. The point here is that the principles of superego are deeply entrenched in the subconscious of each person, often without them being aware of it. The superego has value in civilizing the human animal, but being a slave to it is detrimental to the basic health of the psyche.

Of course, having an innate sense of right and wrong is a natural characteristic of a more evolved human psyche – what we can call ‘conscience’. But conscience is not the same as superego – it is essentially love and empathy. While superego represents a type of morality that conditions our perception of right and wrong based on relative and often artificial principles we have acquired from society, our conscience is based on our basic sense of goodness and natural compassion for others. Morality is linear and cannot reconcile many contradictions in life, and thus often creates conflict and guilt. Conscience does not create contradictions because it does not adhere to rigid rules of behavior or try to be ‘perfect’.

As an example of how conscience operates, there are times when people claim to feel hurt by our actions. But it is not necessarily because we have actually hurt them, but more because they have triggered an emotional reaction within themselves based on certain internalized ideas or past experiences. This is a common issue in relationships. If we approach the situation from the place of natural compassion, we will not indulge in feeling guilty or regretful. Rather, we will simply accept other peoples’ limitations and different emotional issues, and move on. The fact that someone responds irrationally or in an immature way should not create a feeling in guilt in us, if our actions were based on what we feel is right. On the other hand, following what is right, our natural truth, should not be used to justify behavior which is self-indulgent or destructive.

The Limitations of the Freudian Model

Freud’s ‘id’ represents the impulses and needs psyche that demand immediate gratification, while the ego (person) has to learn how to mediate between id, the external reality and the superego. However, there are also needs of a higher degree that the Freudian model doesn’t account for. For these higher needs to be fulfilled, the person has not only to be in his mediating role (between the id, reality, and the superego), but, within reason, has to challenge the collective mind of society and rebel against being imprisoned in his own superego. For instance, having spiritual desires, such as wishing to establish our pure nature, is not part of the id, even though we might feel an urgency to fulfill such desires. Here, the person, too, has to mediate between reality (which may include finding the means to devote ourselves to the inner path, as well as coming to some kind of agreement/compromise with people we care about who may not share similar spiritual desires) and having a realistic perspective concerning the inner reality, where dedication and patience are required to reach our spiritual goals.

Freud saw ‘ego’ too one-sidedly as a mediating agent, rather than what is – a creative force in its own right. Our desires are the force underlying our lives, and aligning them with our higher purpose is also a function of ego. Furthermore, our superego is not crystallized and fixed during our childhood, as Freud suggested. It can change and be changed, based on all the influences we are subject to throughout our lives, plus how we respond to them. For instance, we can create additional layers of superego through our adult choices, such as becoming part of a sect, political movement, or religion. In other words, no matter how much we have been conditioned in childhood, we can choose to either worsen or improve our condition in adulthood through the decisions we make.

Another thing that is missing in the Freudian model is the distinction between the subconscious mind and the subconscious of the person. As we explained, the subconscious of the person is what has already been subconsciously integrated in the person’s character including basic predispositions acquired from personality. Conversely, the subconscious mind includes the subconscious intelligence of the person that is linked to our personal memories, education and history. For instance, the id, or the instinctive desires related to pursuing pleasure and satisfying of our basic needs, is also part of our subconscious mind. But the subconscious mind gradually also develops higher desires which are beyond the id, and the superego, too, becomes part of its structure. In other words, the subconscious mind has to do with our psychological activity, while the subconscious of the person defines how the person is experiencing himself, or who he is.

Furthermore, the conscious, reflective part of the person is not merely mediating between the id and the superego but is also able to create higher desires and transform the subconscious mind by giving it constructive feedback. Among other things, the conscious person can give feedback to the superego, challenging its conditioned notions and dissolving many of its layers. For Freud, the superego was something fixed, but this is obviously not true. Our relationship with the superego evolves as we evolve: some parts of it are rejected, while other parts are accepted as positive elements that we have acquired in the process of learning from society.

The superego exists in the subconscious mind, but it is being reflected in the person. For instance, if the subconscious mind interprets our actions as being ‘wrong’, ‘improper’ or even ‘sinful’, it has an immediate sense of guilt, but this sense of guilt is then transferred to the person who becomes the actual subject, the experiencer, of that guilt.

Conclusion

At present, the provisional map of the psyche is composed of the following elements:

The subconscious mind, which includes:

- the unlearned collective base – what is instinctive and autonomic, including the id, one’s basic impulses and drives.

- the layers of the personal – that which has been learned as an individual, but which operates on a subconscious level.

- The superego – the social and moral standards that condition our sense of right and wrong.

The person, or ego, which includes:

- the subconscious of the person, which is linked to the subconscious mind but is also independent of it, and which is responsible for creating various emotional states and moods in the person,

- the conscious-reflective part of the person (the personal center of intelligence) which is responsible for giving feedback to the subconscious mind and to its own subconscious emotional states and moods.

Blessings,

Aadi

For a definition of the terminology used, please visit the Glossary page. Click here for a printable version of this article.