Ramana Maharishi

No one succeeds without effort… Those who succeed owe their success to perseverance. –Ramana Maharshi

Ramana Maharshi was one of the greatest sages of all time. We say this not so much because of his teachings, but because he was such a highly realized and evolved soul. He entered the path at an early age due to a profound and spontaneous shift in consciousness. Later, he described his awakening as having occurred through intense self-inquiry, in which he visualized that his body had died. However, this inquiry was more a post-awakening rationalization of his inner transformation than its catalyst or cause. Due to this misrendering of events, Maharshi put too much emphasis on self-inquiry later on in his life, wrongly assuming that it could manifest the same kind of awakening in others.

Self-Inquiry – the True Path of Maharshi?

A great number of seekers since have imagined that by following the practice of ‘vichara’ (self-inquiry) they were walking the path laid by Ramana. But were they getting any closer to their true self? Asking oneself ‘Who am I?’ does not constitute a spiritual practice in itself. The true meaning of self-inquiry is to turn consciousness back on itself and directly recognize the essence of pure subjectivity. One cannot unveil the answer to this question through the power of the mind: it is the act of a single instant of pure cognition which is performed by a much deeper faculty than the ‘thinker’. Taken out of this context, self-inquiry can quickly become a mind game, a form of procrastination and avoidance of meeting one’s essential self. Additionally, even if one does inquire correctly, one already needs to have access to the state beyond the mind. Otherwise, who is recognizing who? The answer to this question is not waiting like a forgotten object, needing to be brought into consciousness through our attention – it must be activated through a deep spiritual shift. Awakening is not merely an act of recognition, it is a dimensional leap into our future self. And for that to happen, the doorway to I am has first to be opened. Without that opening, self-inquiry is the wrong practice.

We can discern through his writings that Ramana did not really know how he arrived at his own realization, and this is actually a common story among spiritual masters. The paths they create for their followers are retrospective attempts to rationalize their own paths, paths they did not fully understand as they were unfolding. Ramana oversimplified his path by assuming that, in his initial spontaneous awakening, he had reached complete self-realization. He never expressed this directly in words but he did imply it indirectly. In reality, however, he only became complete after many years of meditation and integration. As a young man, he lived a life of extreme absorption, neglecting his basic human needs. During that time, neither his mind nor his energy were fully balanced. He was intoxicated with the divine, hovering between the shores of enlightenment and madness. He was on his path, his journey, and to think that he was already complete from the beginning is very naive.

He did say once that, from his awakening as a boy right through to his old age, there was the common thread of that which does not change. This is true of the spiritual path – from our entry right through to completion, we carry the thread of the essence of pure subjectivity. But for that essence to become a complete soul, many elements need to fall into the right place. When the seed of a tree is planted, its essence is naturally incorporated into the tree it grows into. However, for the tree to become mature, it has to pass through many long seasons. To confuse Ramana’s initial awakening with his complete enlightenment is to confuse the seed with the great tree it eventually becomes.

Limitations of Ramana’s Path

Ramana was a beautiful being, loving and compassionate and as a teacher, free from any traces of promoting a personal agenda. It is also true to say that he did not experience a normal human life, he did not live in society, pursue any ambitions or seek emotional fulfillment. He tended to avoid any confrontations within ashram life, which may have been due to an accepting attitude or to a type of avoidance of those human dilemmas. It’s interesting to wonder how a person who lived a life of such extreme renunciation could ever understand what it means to be human, or indeed, ever understand other humans. This was the journey he chose, and that is to be respected. However, it is important to see its limitations as well. His contribution to human spirituality was incomparable, but ironically, he could not really understand what it means to be human, because he never lived or developed as one himself, with all the challenges and experiences such a life entails.

As was noted, Ramana taught the path of self-inquiry. But did he really? What was Ramana’s real teaching? He was astute, and he no doubt noticed that none of his devotees were coming any closer to awakening through the practice of vichara. Perhaps he gave them this practice more to keep them busy than to lead them toward a true awakening. There is nothing particularly harmful in self-inquiry, and when it is done in moderation, it can support the maturation of our spiritual intelligence. But in the end, it was not self-inquiry but his powerful presence in conjunction with sitting in meditation that facilitated spiritual progress among his followers.

Ramana’s model of awakening was quite simple, although it did seem to oscillate as time went on. At times he appeared to be teaching a form of sudden enlightenment, while at other times he spoke of its gradual stages. For instance, he differentiated between ‘sahajanirvikalpa samadhi’ and ‘kevalanirvikalpa samadhi’; in the latter, one has access to – but is not fully established in – the self, while in the former, the state is permanent and integrated. He also spoke about an evolutionary curve in which the self is first realized in the head and then drops into the heart. He was not particularly interested in elaborating on the apparent contradiction between the sudden and gradual approaches to enlightenment. We must remember that he was not conscious of all the steps in his own intricate process of completion: most of his evolution happened naturally and spontaneously while he was immersed in samadhi for all those years.

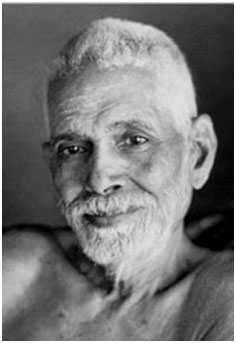

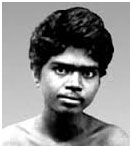

When you look at photos of Ramana when he was young, you can see that all his energy is in his head. There is also an excessive intensity in his eyes, which is an indication of abiding in an unnatural or mystical state. Over time, this intensity dissipated and his eyes came to embody a condition of rest and calm. You can also perceive a sense of alienation in his eyes, coming from his total withdrawal into the inner realm. As his evolution continued, his energy gradually dropped into his heart, which he called the seat of the self (interestingly, he experienced his heart on the right side of the chest, whereas the spiritual heart for a human soul is located in the middle. This is most likely due to certain predispositions that he developed in former lifetimes). Ramana sat in meditation all of his life and as such developed a natural connection to being. Also, while his energy dropped from the head into both the heart and being, his heart was eventually established as the focal point of his existence. So it is clear he was evolving. In Advaita, the concept is that once enlightenment is reached it is complete because any further evolution would imply imperfection, and hence duality. But this, as we have established elsewhere, is far from the truth.

When you look at photos of Ramana when he was young, you can see that all his energy is in his head. There is also an excessive intensity in his eyes, which is an indication of abiding in an unnatural or mystical state. Over time, this intensity dissipated and his eyes came to embody a condition of rest and calm. You can also perceive a sense of alienation in his eyes, coming from his total withdrawal into the inner realm. As his evolution continued, his energy gradually dropped into his heart, which he called the seat of the self (interestingly, he experienced his heart on the right side of the chest, whereas the spiritual heart for a human soul is located in the middle. This is most likely due to certain predispositions that he developed in former lifetimes). Ramana sat in meditation all of his life and as such developed a natural connection to being. Also, while his energy dropped from the head into both the heart and being, his heart was eventually established as the focal point of his existence. So it is clear he was evolving. In Advaita, the concept is that once enlightenment is reached it is complete because any further evolution would imply imperfection, and hence duality. But this, as we have established elsewhere, is far from the truth.

Ramana was living in samadhi, not only when he sat in meditation, but at all times. He didn’t have the conceptual tools to explain his state, but in our terminology we would say it was a combination of consciousness, heart and being. While he was not on the path of the absolute state, the depth of being he reached was enough to absorb his consciousness and heart into the state of absence. Because of the greatness of his soul, by the end of his life he did become whole and complete, despite having completely disregarded his human nature and individuality. And although he did become whole, he did not teach a path to wholeness, but rather a path to transcendence. He was a pure channel of Shiva and the last true teacher of Advaita, a spiritual titan amongst men. He will forever be remembered as the embodiment of the highest spiritual potential of humankind.

Having said this, to follow his teaching without his direct presence does not offer a clear path of evolution. While he did insist on the practice of sitting meditation, he did not clearly explain what meditation really is or how to cultivate the inner states. So he was not a meditation teacher. His concept of transforming thinking was to ‘kill the mind’ and to ‘kill the ego’, an approach which not only does not work, but prevents any possibility for the positive transformation of our human self.

The limitations of his teaching can be simplified and summarized as follows: lack of the knowledge of me (not just its multidimensional nature, but even a basic insight to what our me really is); denial of our individuality with the resulting extreme identification with the impersonal; lack of distinction between awareness and consciousness; incomplete vision of vertical evolution (other than consciousness dropping to the heart); lack of embracing our human existence or a conceptual vision of how to integrate it with our higher self; simplistic and one-dimensional concept of the mind (in which an understanding of how consciousness and thinking coexist was entirely absent); and last but not least, an absence of the concept of soul, our higher individual self. Ironically, while he based his teaching on self-inquiry, he failed to give an accurate answer to the question ‘Who am I?’. He plunged into the realm of the universal I am, but he did not acknowledge his soul as the subject of unity with the self. This is what we call the confusion or displacement of identity.

Ramana taught through his grace and the grace of Shiva. Ultimately, it was his presence which transformed his devotees. It was his continuous absorption in the self, his love and uncompromising representation of the light of consciousness and the transcendental energy of Shiva, which made him the greatest of sages and greatest of masters.

Nisargadatta Maharaj

“There is nothing to practise. To know yourself, be yourself. To be yourself, stop imagining yourself to be this or that. Just be. Let your true nature emerge. Don’t disturb your mind with seeking”

–Nisargadatta Maharaj

Nisargadatta Maharaj was a unique and great being, although very different in temperament and approach to Maharshi. Unlike Ramana, he did have a master, Siddharameshwar Maharaj, who belonged to the lineage of the ‘Nine Masters.’ However, his master passed away very soon after initiating him into his practice, so Maharaj had to continue his path alone. His teaching was born out of this aloneness even though, as with Ramana, it was supported by the non-dual construct of reality. The main instruction he received from his master was to keep the sense of ‘I am’ at all times, which he did until he reached stabilization in consciousness. This took him three years. Although he never revealed the details of his own path, his personal development continued for many years after that.

Maharaj was known for his fierce temperament, chain smoking and disregard for convention. Some visitors judged him for his ‘unsaintly’ lifestyle, incessant smoking and consumption of meat. But he did not care – he was just himself. His style of speaking was Zen-like, abrupt, sharp and to the point. As can be seen from his books, his teaching remained effectively the same from its original conception forward. This is the case with many masters – they simply stop evolving.

“I Am That”

Maharaj was completely unknown in the West, and even in India, until Maurice Frydman (one of his closest disciples) published the book I Am That, a compilation of recorded talks gathered over the course of several years. While I Am That is widely considered to be his seminal work, and a spiritual classic, it is important to be clear that it doesn’t really represent Maharaj’s own teaching. It was written in Frydman’s own words and carries his very eloquent style, and as such is only loosely based on what Maharaj himself said. Maharaj was a simple man whose manner of speaking did not have the sophistication and poetic power of I Am That. But this in itself does not make this book any less valuable.

I Am That is one of the most beautiful books ever written. Having said this, it is also completely impractical (similar to the Tao Te Ching). It may be a source of inspiration and have a deep and supportive spiritual energy, but it cannot directly help anyone actually awaken. In fact, it is the kind of book which creates the illusion that one has understood something, while in truth, one has not understood anything at all. Beauty can be deceiving. The words in I Am That weave an enchanting spell of spiritual understanding, and yet at the end, one is left empty-handed. It is one of the most lovely and useless books ever written on the subject of enlightenment. However, if its purpose was to attract western seekers to Maharaj, it has done its job.

Path of Maharaj – Transcending ‘I am’

The teaching of Maharaj contains both the traditional elements of non-dual teachings and his own personal discoveries. Because he walked the majority of his path alone, Maharaj needed to use his own discriminative intelligence in order to measure his progress and to identify any missing elements. His deepest longing was to reach complete freedom from manifestation. He was not interested in becoming whole or in obtaining peace on the human level, but rather in attaining complete and absolute disidentification from phenomenal existence. As he moved deeper, he was effectively peeling away each layer of identification with the body and mind until nothing was left. On some level, this process resembles the teachings of the yoga sutras, which culminate in reaching ‘nirbija samadhi’ (literally ‘seedless samadhi’). This subject will be explored in a later article on the yoga sutras.

In his practice, Maharaj was not just abiding in the knowledge of I am. As Buddha before him, he incorporated the additional element of contemplation into the relative nature of consciousness and causes of bondage in the realm of illusion. In doing so, he was ‘receding’ his sense of self further and further into the absolute base of universal subjectivity. He utilized the power of will to keep disidentifying more and more strongly and deeply from the relative dimension. In the end, he realized that even pure consciousness is flawed, and one has to go beyond I am in order to reach true freedom. This was the novel aspect of Maharaj’s teaching – that I am is not the absolute. According to Hinduism, the nature of Brahman is sat-chit-ananda or being-consciousness-bliss. For Maharaj, sat-chit-ananda represented a layer of reality that needed to be transcended – the final sheath of illusion. His concept of the ‘absolute’ pointed to the state prior to sat-chit-ananda, the state prior to consciousness.

What exactly did Maharaj mean by the ‘absolute’? Was he using the term as we do in our teaching, to point to the unmanifested source of consciousness and creation, realized through the portal of being? Conceptually this would make sense. However, the path of Maharaj was not a path of being. In fact, Hindu spirituality in general does not have a strong connection to the dimension of being. It is a path which tends to elevate energy upwards, toward the higher centers. In truth, only Taoism and Zen are paths of being, as they aim directly at evolution toward the source through the portal of tan t’ien.

So what was the absolute for Maharaj? How can consciousness go beyond consciousness? How can one go beyond the knowledge of I am? Who is going beyond what? This is a deep paradox, and unless it is understood, the teaching of Maharaj cannot be grasped properly. The problem is that his realization cannot be explained through the conceptual tools present in either Advaita or Buddhism, because their visions of the nature of consciousness lack some very important components. Consciousness has several dimensions which are in relationship with both creation and the universal I am. When we contemplate the concept of going beyond consciousness, we must first realize understand that the whole process of awakening is actually about awakening a consciousness and identity that are existentially higher than those of our present condition. For instance, what does it mean to go beyond the observer? It is to awaken conscious me. What does it mean to go beyond conscious me? It is to awaken pure me. Pure me then surrenders to the universal I am of consciousness in order to reach complete absorption and manifest pure consciousness.

When Maharaj spoke of transcending consciousness, which dimension of consciousness was he referring to? He was referring to pure consciousness. So how can pure consciousness be transcended if it is already realized through surrender into the universal I am? Pure consciousness can be experienced on two levels – on the level of presence and on the level of absence. On the level of presence, pure consciousness is indeed in the condition of surrender to I am, but that surrender is incomplete. It is because of that surrender being incomplete that Maharaj identified his consciousness as still imperfect, meaning not free from suffering. The state prior to consciousness, to which Maharaj referred, was in fact pure consciousness realized on a deeper level as horizontal samadhi in the universal consciousness. This explains why he maintained there is the quality of inherent knowing in that state beyond consciousness. To reach what he called ‘the absolute’ is not merely to disidentify from the lower realization of pure consciousness, but to surrender deeper into I am in order to actualize horizontal absence. Horizontal absence in universal consciousness is realized through the portal at the back of the head.

When an adept attains pure consciousness, it is invariably incomplete for a number of potential reasons: pure me is not awakened so he cannot embody the state, conscious surrender to I am is missing, so the state is shallow horizontally, or the vertical dimension of surrender and restfulness in consciousness is lacking. In any of these scenarios, one is merely abiding in consciousness, or experiencing it as the background of one’s ordinary sense of me. Just to abide in consciousness is to remain locked in the dimension of presence, and it is this kind of consciousness that Maharaj wanted to transcend. In short, the state prior to consciousness to which Maharaj referred is not the unmanifested but rather consciousness in complete absorption in the universal I am. It is so absorbed in absence that it feels like the absence of consciousness, while retaining the quality of being conscious of itself.

The deeper state prior to consciousness is the true absolute state, the final fathomless depth of being. This absolute state is realized through an entirely different doorway, which is located in tan t’ien, in the lower belly. It is prior to consciousness because there is no consciousness in it, only the pure isness of existence steeped in absence and in the absence of absence. Of course, when the absolute is realized, consciousness illuminates it with the light of knowing, so that it becomes part of our conscious experience of reality. But this is not what Maharaj was experiencing, nor was it part of his teaching.

What did Maharaj mean by ‘ I am?’

Another matter to contemplate is the actual meaning of ‘I am’ in Maharaj’s teaching. What ‘I am’ was Maharaj maintaining when he was given this practice by his guru? Words are relative and deceptive. In order to become the proper tools for communication, they need to be carefully defined. In our teaching, we used to use the term ‘I am’ to signify slightly different things depending on the context: the soul, pure consciousness, and the impersonal universal self. However, as the teaching has evolved, and our terminology has become more precise, the term I am is now used only to denote the universal reality. I am signifies the existence of the divine, the ultimate counterpart for our me.

No one has ever really questioned what Maharaj meant by this term, and yet each person who speaks of ‘I am’ may in fact be referring to entirely different aspects of our existence. Being such a subtle and hidden dimension, the true meaning of I am cannot be obvious to the average reader or practitioner. As such, the fact that Maharaj’s use of the term has not been explored or explained shows a lack of basic inspiration and spiritual sensitivity. In fact, it appears that most people translate ‘I am’ within their own experience as their sense of me in the mind. In that case, someone who was practicing self-remembrance would actually be trying to maintain their self-conscious observer. While this has some validity on a lower level, it is obviously very different to maintaining the consciousness of I am.

Maharaj was not only told by his guru to ‘keep’ I am, he was initiated into I am, meaning his master transmitted the awakened state to him. That which he called ‘I am’ was pure consciousness, realized on the level of presence. However, he was not awakened to pure me, nor did he consciously know that he had to surrender to universal consciousness. He was just ‘keeping’ the state of pure consciousness through a form of self-remembrance. The whole process was happening by itself, without its various intricacies being grasped by his inner intelligence. Eventually, he did realize his soul, but not in a conscious way. He was surrendering to the universal I am from his pure me, but due to the preconceptions he inherited from Advaita, he did not recognize who was surrendering and who he had become as a result of that surrender. His soul-awakening was not conscious, because he did not long to meet himself – all he wanted was to reach freedom.

Nisargadatta was a rebel. He did not care about fitting into anybody’s ideas of sainthood on the human level, nor did he adhere blindly to any Hindu traditions or concepts.

In many ways he went beyond Hindu idealism in his conviction that sat-chit-ananda was not the highest reality. He did not believe in reincarnation either, which is very much at the root of the Hindu view of reality, but rather spoke about I am as the ‘essence of food’ born of the physical body. In his view, when the body dies, so does I am. So his perception of consciousness was unusually ‘materialistic’.

Limitations of Maharaj’s Vision

Due to their non-dual preconceptions, neither Ramana nor Maharaj understood that we are in a dynamic relationship with the beyond. Through their spiritual inquiries, they tried to affirm their own nature as the ultimate, failing to grasp the intricate difference between awakening and surrender. How can we surrender to the universal reality and enter the realm of absence if we do not know who surrenders, if we not only deny our own existence, but also deny that the beyond is internally-external to us? Here we can see clearly how incorrect visions of the path and reality can handicap evolution into complete realization. We must remember that there is no conscious surrender in Advaita, because it has no concept of the beyond. To speak of surrender, we must affirm our own existence first, and only then the existence of the universal reality as our transcendental subjectivity. Without acknowledging that higher duality, who is there to surrender to whom?

Our vision of reality has to reflect reality, or it becomes a construct of the mind that superimposes itself on our existence, thereby distorting our realization of it. Of course, the mind is part of total existence, but only that mind which, through the evolution of its intelligence and internal purification, has come to reflect the truth of that which lies beyond the frontiers of conceptual thinking. Any other mind is the enemy of reality. Even though Maharaj had a deep wish to reflect truth in his intelligence, he could not free himself from these very entrenched non-dual preconceptions. He questioned many things, but somehow did not question the very impersonal foundation of his perception. This is not surprising, considering his total dislike of creation and wish to dissolve fully.

Maharaj spoke of three layers of consciousness: ‘vyakti’, ‘vyakta’, and ‘avyakta’. Frydman translated avyakta as ‘awareness’ but this a very bad translation. For some reason, Frydman saw awareness as higher than consciousness, but it is consciousness that is existentially deeper. Words are relative signifiers, but we should use them in a way that resonates sensitively with what they point to. The term ‘aware’ originates from ‘beware’ and its meaning therefore naturally links to the attention of the observer and its need to survive. Consciousness comes from the word ‘conscrire’ which means ‘to know’ – the word itself reflects the faculty of pure knowing inherent to our pure nature. What Maharaj meant by avyakta was in fact ‘nirgunabrahman’ or ‘parabrahman’ – the unqualified absolute. To translate it as awareness is misleading.

Vyakta is translated as the ‘inner self’ or ‘I am’, and vyakti as the ‘outer self’ or ‘the ego.’We could say that vyakta is like the soul or our higher individuality, a bridge between vyakti and avyakta. But Maharaj saw it differently, as a place of a passage to complete impersonality. At times, he equated vyakta with brahman and avyakta with parabrahman. In his view brahman was limited because it still possessed the ‘sheaths’ of sat-chit-ananda. Meister Eckhart, a Christian mystic, made a similar differentiation between ‘god’ and ‘godhead’ where godhead represents a place in the ultimate where even god himself cannot enter. This is the inner shrine of the heart of creation, the place prior to the arising of consciousness or cognition. In our teaching, godhead or ‘avyakta’ is the absolute, the pure isness of the source while the divine, universal consciousness (and intelligence), and universal me represent the emanations of that source into creation.

What Maharaj failed to recognize is that without vyakta there is no avyakta. He refused to embrace his true individuality, because, it appeared to be too strong a link with his personal self. As long as there is vyakta, there is vyakti (the personal me). But how can vyakti be transformed unless we embody our higher individuality as an essential step in our evolution toward wholeness? No wonder he seemed so ill at ease on the human level. The human in him could not surrender to his higher self, because he denied its validity and existence.

We can appreciate the sharpness of Maharaj’s process of elimination from the relative to the absolute, from vyakti to vyakta and, finally, to avyakta. But this abrupt elimination and quest for transcendence turns against the very purpose of our existence – to actualize our divine individuality. Avyakta does not need us to realize himself; he has always been perfectly fulfilled. So who is realizing what?

Did Maharaj truly actualize the I am he spoke of so much? Yes and no. He certainly did not embody I am as his soul. Rather, he stepped into I am in order to go beyond it and lose himself in samadhi. He failed to see that what he called avyakta was in fact an immaculate unity of vyakta and avyakta. His urge for self-denial was so great it went against him.

Grace of the Master

Maharaj’s only teaching was to ‘keep I am’ in the hope that at some point one would be miraculously able to stabilize it and then go beyond it. He did not clarify what I am was supposed to be, or even whether it was to be found in the head or heart. The methodology of his teaching was close to that of ‘jnana yoga’ (yoga of knowledge) which is an approach that relies exclusively on intense inquiry to obtain insight into one’s absolute nature. In Maharaj’s view, it was through complete understanding of, and total conviction in, one’s pure nature that one somehow comes to embody it. But of course, this does not really work. No inquiry or conviction of any sort can manifest the awakening to our pure nature, and especially not to the state prior to consciousness. Though Maharaj spoke persuasively and with great passion about awakening, he did not develop or offer any practical tools that could serve as a bridge between ignorance and enlightenment to others. As such, we could say that, as with Ramana, his real teaching was entirely based on his presence and grace. It was his powerful consciousness and inexorable dedication to truth that served as the transformative force for his more mature and sincere devotees.

Acme and Ending of Advaita

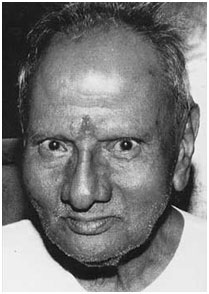

It is common to view Ramana and Maharaj as the two prominent masters of the Advaita tradition. However, itmust be kept in mind that they were not walking the same path, and that their realizations were quite different. The samadhi Maharaj reached was primarily in universal consciousness. It is for this reason that his eyes were so intense: his consciousness in conjunction with the depth of surrender and absolute disidentification was like a living fire. Ramana did start with awakening to consciousness, but he realized it in a different way, sitting in meditative absorption. When he was young, his eyes were also over-intense, but that changed over time. As he matured and grew older, his consciousness relaxed and dropped into his heart.

Another interesting point is that Maharaj did not incorporate any rigorous meditation training into his path. He was practicing in activity, in everyday life. If he did sit in meditation, it was done in moderation and mostly involved the contemplation of consciousness. Maharishi on the other hand, sat in deep meditation for twenty years. Therefore his energy naturally dropped more into being and the vertical dimension of his self was more awakened than that of Maharaj. It is possible to perceive a certain mystical element in Maharaj’s eyes, which indicates, that his state was not fully natural. Due to his extreme practice of disidentification, and to the fact that he did not sit, he developed consciousness that was too intense and lacked the vertical dimension. It is likely that mixing it with these mystical elements allowed him to cope with that intensity, because this helps to dilute the sense of me by ‘spacing it out’ thus making one less self-conscious of any energetic discomfort.

They were two different people, even if they were both connected to the energy of Shiva and Advaita. Maharishi was more in harmony with his human nature, more at peace and rest. Maharaj was living on the edge all his life; his was a path of intensity. Maharishi was a saint, for the good and for the bad. Maharaj was a rebel and spiritual revolutionary. He challenged the whole concept of spirituality, morality and sainthood in his total and absolute approach to transcendence.

Ramana and Maharaj were both great beings who deeply embodied the light of the self, while uncompromising serving through their very existence the revelation of truth. However, it comes as a surprise that in spite of their enormous spiritual capacity and intelligence, neither of them were able to embrace and understand the consciousness of me and decode the higher goal of our evolution beyond non-duality: the actualization of our soul. This only goes to show how deep human spiritual conditioning is. If these two beings could not transcend their conditioning, what can we expect from the average seeker? Perhaps their role was more to complete and end the era of Advaita. Since their deaths, no one has come even close to carrying this amount of light in the name of non-duality. Once upon a time, Advaita was a breakthrough revelation in human spirituality. But once this revelation was digested in the collective consciousness, it had served its purpose. Now it can be transcended. A new understanding must enter this dimension, a deeper revelation of truth, beyond the one-dimensional vision of spiritual evolution of non-duality. We have great love for Ramana and Maharaj, but it is time to move on. They gave us so much and they failed us so much too, by denying the existence of the soul. In their conditioned pursuit for self-knowledge, they missed the very essence of that knowledge – me.

Blessings, Aadi

For a definition of the terminology used, please visit the Glossary page. Click here for a printable version of this article.