Awakening is possible only for those who seek it and want it, for those who are ready to struggle with themselves and work on themselves for a very long time and very persistently in order to attain it.

— Gurdjieff quoted in P.D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff was an extraordinary self-made man who developed a unique system of teaching during his many years of travels, studies, and experimentations in his work with students. He had the rare quality of originality in this world of imitation. His great passion for learning and understanding truth encompassed the study of many of the spiritual systems he encountered in his personal search, including Sufism, Tibetan Buddhism, Hinduism, and Yoga, as well as some of the then current European and Russian occultism. He did not study to collect information as an academic, but rather to discover what was real and useful to his own development and to his work with students.

The Work: Waking Up From Sleep

Without self knowledge, without understanding the working and functions of his machine, man cannot be free, he cannot govern himself and he will always remain a slave. . . . . . . Let us take some event in the life of humanity. For instance war. There is a war going on at the present moment. What does it signify? It signifies that several millions of sleeping people are trying to destroy several millions of other sleeping people. They would not do this, of course, if they were to wake up. Everything that takes place is owing to this sleep. . . . . . . A man is responsible for his actions, a machine is not responsible.

— In Search of the Miraculous

Development was the key word of Gurdjieff’s approach. It was all about doing what came to be called ‘the Work’. He was particularly skillful in describing the state of ignorance of an ordinary man, whom he called the ‘man-machine’. A man-machine is someone who lives in the illusion of being in the waking state while actually being deeply asleep. In Gurdjieff’s view, even those who called themselves spiritual, religious, moral, or pious were all asleep. A man-machine believes he has discrimination and the free will to make his own choices, but this is just an illusion. He has no freedom of choice, because the whole structure of his mind is entirely conditioned and mechanical. For instance, an individual may believe that he is a Christian, a Jew, or a Buddhist, and may also imagine that he has defined himself in that way based on his free will. But people like this are really just machines, an unconscious herd, passively absorbing concepts from their environments, and mechanically reacting to their external and internal circumstances. No one thinks for himself. They are puppets of the collective mind, without any authentic self or individuality. In short, each one is just a machine. The purpose of the Work was to stop oneself being a collective, unconscious robot and to wake up from that sleep. Although the concept of awakening was not a novelty, Gurdjieff’s own understanding of it and the methods used in his teaching were unique.

The Fourth Way

The method of the fourth way consists in doing something in one room and simultaneously doing something corresponding to it in the two other rooms – that is to say, while working on the physical body to work simultaneously on the mind and the emotions; while working on the mind to work on the physical body and the emotions; while working on the emotions to work on the mind and the physical body. . . . . . On the fourth way it is possible to work and to follow this way while remaining in the usual conditions of life, continuing to do the usual work, preserving former relations with people, and without renouncing or giving up anything.

— In Search of the Miraculous

Gurdjieff created the concept of the fourth way. In his view, there were three principal ways in spirituality: the paths of the fakir, the monk, and the yogi. He gave them rather simplistic interpretations: the fakir’s is the path to realization through the body, the monk’s is through devotion (work with emotions), and the yogi’s is through knowledge (the mind) Gurdjieff’s use of the term ‘monk’ was probably more related to Christianity. Obviously a Buddhist monk would not fit this description. Also, the path of the yogi is more a path of internal discipline than of knowledge, with the exception of jnana yoga.*. However, because all three ways were based on renunciation, he proposed a new solution that would incorporate the Work into everyday life. This was his fourth way. According to the fourth way, we must awaken our essence – which has been lost in our false personality – in everyday real life.

Gurdjieff’s understanding of how the human identity is constructed is as follows:

It must be understood that man consists of two parts: essence and personality. Essence in man is what is his own. Personality in man is what is ‘not his own.’ ‘Not his own’ means what has come from outside, what he has learned, or reflects, all traces of exterior impressions left in the memory and in the sensations, all words and movements that have been learned, all feelings created by imitation – all this is ‘not his own,’ all this is personality.

— In Search of the Miraculous

There are, in fact, four layers to our identity: false personality, personality, essence, and the real I. False personality is the personality of the man-machine, totally disconnected from essence. The positive, as opposed to the false, aspect of personality is our psychological constitution that is being expressed in connection to the real I. Essence is the core of our existence and is not bound by our countless conditionings and relative tendencies. When this essence is fully actualized, it becomes our real I. Gurdjieff said that man is not born with a soul, and that the soul has to be developed in order to come into existence. His concept of essence allows us to better understand this statement. Each one is born with essence, which is the unconscious seed of the soul that must then be actualized through the conscious work of awakening.

The Man-Machine Has No Soul

That must be understood very clearly. Man cannot do. Everything that man thinks he does, really happens. It happens exactly as ‘it rains,’ or ‘it thaws.’ . . . . . . Man is a machine, but a very peculiar machine. He is a machine which, in right circumstances, and with right treatment, can know that he is a machine, and having fully realized this, he may find the ways to cease to be a machine. . . . . . . Man has no individual I. But there are, instead, hundreds and thousands of separate small I’s, very often entirely unknown to one another, never coming into contact, or, on the contrary, hostile to each other, mutually exclusive and incompatible. Each minute, each moment, man is saying or thinking ‘I.’ And each time his I is different. Just now it was a thought, now it is a desire, now a sensation, now another thought, and so on, endlessly. Man is a plurality. Man’s name is legion.

— In Search of the Miraculous

Gurdjieff was the first teacher ever to state clearly that we are not born with a soul. In reality, what we have is just a dormant essence; our soul is non-existent. Gurdjieff went on to say that only by developing the soul can one be immortal, and that those who exist prior to self-remembrance may simply cease to exist upon death.

He may live through all his life as he arose and was crystallized thanks to all kinds of influences eventually forming the conditions of life around him, and as such after death be destroyed forever.

— Gurdjieff, Life is Real Only Then, When “I Am”

Gurdjieff goes on to quote Persian verse:

If all men had a soul, Long ago there would have been no room left on earth for poisonous plants or wild beasts, And even evil would have ceased to exist.

So as we can see, Gurdjieff expressed views that could be alarming to those who naively believe the soul to be our birthright. But he was far from being idealistic. He based his theories on deep study of human nature and many years of personal experimentation. He also saw that some people just cannot awaken, no matter what they do, either because of their lack of potential or the pull of their lower tendencies:

Speaking thus about it, I consider it my moral duty here to add and particularly to underline that, although the said liberation is possible for man, not every man has a chance to attain it. There are a great many causes which do not permit it and which in most cases depend neither upon us personally nor upon great cosmic laws, but only upon various accidental conditions of our arising and formation, among which the chief are of course heredity and the conditions under which the process of our ‘preparatory age’ flows. It is just these uncontrollable conditions which may not permit this liberation.

— Life is Real Only Then, When “I Am”

The paradox is that prior to the development of their higher self, people do not really have free will. Therefore, they cannot really be blamed or condemned for being stuck in their lower nature. Only those who have come to the threshold of having real freedom of choice, and then do not choose their higher intention, can be subject to judgment.

Unless we begin evolution toward individuality, we are not really living at all – we are vegetating. For Gurdjieff, to live in ignorance is to live in disconnection from the wisdom of creation. The one who lives in a mere illusion of having ’I’, lost in forgetfulness and his false personality, not only does not have control over his destiny, but is also beyond help from existence. Neither life nor grace can reach out to him. As Gurdjieff says, he lives “under the law of accident”. In combination with his mechanical mind, he is the sum total of all the influences around him. He is a Christian because he is accidently born in a Christian country. He is a Buddhist because he is accidently born into a Buddhist family. He is a Jew because his parents were Jewish. He is a robot. He does not know why things are happening to him because he is himself an accident. To become real and transcend the law of accident, man has to awaken to his essence and begin the work of growing into his individuality. That is his only salvation.

From Self-Observation to Self-Awareness to Self-Remembrance

Not one of you has noticed the most important thing that I have pointed out to you. That is to say, not one of you has noticed that you do not remember yourselves. You do not feel yourselves; you are not conscious of yourselves. . . . . . . In order really to observe oneself one must first of all remember oneself. Try to remember yourselves when you observe yourselves and later on tell me the results. Only those results will have any value that are accompanied by self-remembering. Otherwise you yourselves do not exist in your observations. In which case what are all your observations worth?

— In Search of the Miraculous

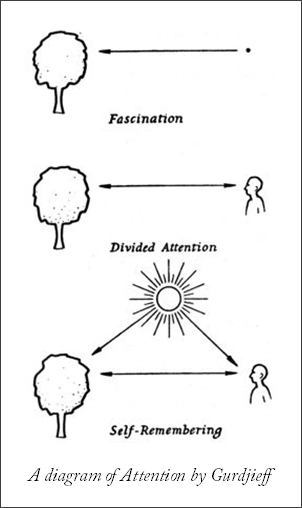

In Gurdjieff’s view, there are four states of consciousness: sleep, waking dream (the illusion of being awake), self-awareness, and objective consciousness. His main work was to activate self-awareness in his students, which is the first step out of being the man-machine. Gurdjieff said that a normal person does not possess a singular ‘I’, but each thought, desire, or emotion creates a separate I. So people have many I’s, each one fighting for dominance. One I wants this, while the other wants something else. In Gurdjieff’s teaching, this is called ‘identification’. One is constantly losing oneself in thoughts, emotions, and objects, unable to separate one’s I from the stream of experiencing.

Prior to reaching self-awareness, one is meant to practice self-observation to identify the illusory character of the false self. Gurdjieff used many methods to activate self-awareness. He often used shock as a device, such as waking his students up in the middle of the night and taking them to some unknown location without reason or explanation. To awaken the faculty of attention, he also employed the Sufi stop-dance in which one totally lets oneself go into dance, but must be ready to stop in an instant when the signal is given, even if that means losing one’s balance and falling down. In this exercise, it is not only the body that stops, but also the mind, and one is meant to have a glimpse of self-awareness in that stop. Gurdjieff also utilized very complex body movements in order to go beyond our automatic motor tendencies and activate our deeper awareness. The final component in his development of self-awareness was the more advanced practice of self-remembrance, which aimed at rendering self-awareness permanent.

Prior to reaching self-awareness, one is meant to practice self-observation to identify the illusory character of the false self. Gurdjieff used many methods to activate self-awareness. He often used shock as a device, such as waking his students up in the middle of the night and taking them to some unknown location without reason or explanation. To awaken the faculty of attention, he also employed the Sufi stop-dance in which one totally lets oneself go into dance, but must be ready to stop in an instant when the signal is given, even if that means losing one’s balance and falling down. In this exercise, it is not only the body that stops, but also the mind, and one is meant to have a glimpse of self-awareness in that stop. Gurdjieff also utilized very complex body movements in order to go beyond our automatic motor tendencies and activate our deeper awareness. The final component in his development of self-awareness was the more advanced practice of self-remembrance, which aimed at rendering self-awareness permanent.

The concept of self-awareness is far from clear, and it was confusing even to his closest disciples who later taught in his name. In the end, no one really grasped in a crystal clear way the fundamental concepts of Gurdjieff’s system, such as self-observation, self-awareness, and self-remembrance. For instance, we find this interpretation from a very well-known teacher from this tradition, Maurice Nicoll, who studied personally with both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky:

Now if man remembers his Observing I, he will observe himself: he will observe he is trying to remember himself – and this will prevent him. It is not the same as remembering himself. If he remembers his business self he will begin to become preoccupied with his business and perhaps ring up someone. The business self feels it can do, just as the observing self feels it can observe. . . . So when we are told to remember ourselves and ask, ‘which self?’ what answer can we expect . . . We can expect the answer: ‘the self that knows its own nothingness.’ This would be a full form of Self-Remembering. The result of work is gradually to make us see that we cannot do. You say: ‘Of course I can do.’ The Work speaks of ‘doing’ differently from the life-idea of doing. For instance, in the Work-sense, to change oneself is to do.

— Maurice Nicoll, Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky

This comment is quite mystifying. While the author seems to be showing that the observer can find no permanent I, this passage in no way indicates he understood the correct meaning of self-awareness. What does it mean to remember the observing I? It is to know directly and to stay with the essence of the subjectivity of attention, its inherent sense of me. This is what Gurdjieff meant when he said, “In order really to observe oneself, one must first of all remember oneself.” The statement, “he will observe he is trying to remember” confuses self-remembrance with self-observation. Self-observation can be done on two levels: one is to observe what is happening in our psychosomatic existence (like what we think or feel), and the second is to observe the act of self-remembering.

On the other hand, if one feels the observer directly, one does not have to activate a second layer of looking at the act of recognizing that observer. And even if one does, these two layers can coexist without conflict. The end of the quotation shows us that, due to unskillful practice, the essence of the observer has slipped out of the grasp of its own attention. Because one cannot maintain concentration in the subjectivity of the observer, and yet is still trying to remember it before it gets identified with any mental formation, this creates a vacuum in recognition that the author translates as the observer knowing “its own nothingness”. In reality, nothing of that sort happens. Self-awareness is something very tangible and contains the naturally solidified sense of pure knowing of that subjectivity. What Nicoll seemed to miss is that the self that is being remembered is the same as the one who is doing the remembering.

Perhaps here we can bring order into the subject of how self-observation is linked to self-remembrance and self-awareness. To be in self-awareness is to be one with the subjectivity of attention of the observer – conscious me. Then observation can be directed to three main areas: external objectivity (such as being conscious of visual perceptions), internal objectivity (being conscious of the body, emotions, and thoughts), and internal subjectivity (being conscious of the act of recognizing the inherent sense of me in attention). In the last one, attention is in a dual relationship with itself through the medium of subtle thought. Beyond internal self-observation lies direct non-dual recognition of attention in itself, which is bare attention of conscious me (now without even the medium of any subtle thought). In our teaching, this stage is followed by the vertical surrender of that attention as conscious me into the condition of abidance in order to awaken its deeper subjectivity – fundamental me. It is important to understand that when the goal of self-observation has been reached and self-awareness is established, one should go beyond the addiction to self-observation in order to open the door to deeper evolution beyond the observer.

What did Gurdjieff mean by self-attention? Some incorrectly equate it with Buddhist mindfulness, but it is more than that. In mindfulness, one is still not in touch with I. In mindfulness, one is still a man-machine – just a mindful man-machine. In Gurdjieff’s self-awareness, mindfulness is included, but one also becomes conscious of the one who is mindful, which is the identity of the observer. Self-awareness is basically the condition of self-attention or self-conscious observer, or when fully mature, conscious me. When the observer becomes conscious of its essence beyond observing, conscious me is awakened. Self-awareness may include active recognition of the body or mind, but its essence is the continuity of self-attention. In mindfulness, there is no self-attention, only attention of what appears in the field of consciousness. So self-awareness goes one step deeper into our subjectivity than mindfulness. Gurdjieff’s self-awareness was meant to lead one to the awakening of conscious me. It is important to understand that self-awareness can be awakened only if attention is isolated in its pure form from any act of self-observation, including inner self-observation. It appears that very few within Gurdjieff’s school understood this.

In addition, we must acknowledge that self-remembrance and self-awareness point to a very limited realization. Gurdjieff’s self-remembrance is shallow because the realization of conscious me lacks the horizontal depth of pure consciousness. The observer is working overtime, and it is very difficult to inspire him to constantly remember himself because he is simply not well; he feels uncomfortably stuck in the prison of the front of the head. Additionally, people who do this practice usually confuse the observer with conscious me; hence they come to activate the observer too much. This practice attracts intellectually oriented seekers, who often lack certain sensitivity. Anyone who is in touch with his deeper existence will soon recognize that self-observation, or even self-awareness, is actually very uncomfortable. Such a practice can be useful at the beginning, but it is not meant to be done for long periods of time – certainly not for years.

From Self-Awareness to Objective Consciousness

The next stage of development in Gurdjieff’s system is reaching objective consciousness. It is not very clear how we are to evolve from self-awareness to objective consciousness. Objective consciousness is described as a condition in which one can experience unity with the external reality and see things are as they are. In self-awareness, one is conscious of one’s sense of me, as opposed to being solely conscious of the environment. This was called ‘double arrow attention’ – being aware of subject and object simultaneously. While very important, self-awareness does not allow one to go beyond the split between subject and object and to experience unity with the world. Reaching such unity is a function of the awakening of a deeper field of awareness in which the duality of the inner and outer can be transcended. In higher self-remembrance, the double arrow attention not only maintains continuity of recognition of the outer and inner simultaneously, but pure consciousness is also remembered and pure me is constantly surrendering to I am – elements obviously missing in Gurdjieff’s teaching.

Using the terminology of our teaching, we can say that Gurdjieff’s self-awareness is a stage in the development of the observer where it can experience itself in separation from thought and begin to awaken conscious me. The observer represents our identification with external attention, which by definition requires an object. So how can the observer experience himself in isolation from the mind and perceptions? There is no contradiction here. Self-awareness is a stage in the development of me where it is in-between being involved in thoughts and perceptions and meeting its deeper subjectivity. Self-awareness, or in our terminology, the self-conscious observer, is half in and half out; it is between the observer and conscious me. It is a transitory stage, and not a place where one would wish to remain forever.

It is harder to identify exactly what Gurdjieff meant by ‘objective consciousness’. Ideally, this should signify pure consciousness. However, there is no evidence Gurdjieff’s work pointed in any way to transcendence of me and surrender to the universal I am. It was all about the development of me in itself. So based on the energy of his teaching and the logic behind his work, we are inclined to identify objective consciousness more as the awakening of awareness. Awareness is a stage in between conscious me and pure consciousness, a horizontal expansion of conscious me that does not cross the doorway to I am at the back of the head.

How does the awakening of awareness correspond to having access to the experience of unity with the outer world? In order to experience any level of unity, we must have the ground of pure subjectivity, a place beyond self-reference (which is inherently dual). For instance, when one is mindful, one can pay complete attention to the outer. However, this does not constitute unity because that attention has no abiding place within our consciousness. It is looking with determination to be present in the act of perception, but it is constantly self-referencing; hence it knows itself to be separate from the observed. True oneness does not require mindfulness. In fact, one can be not mindful at all and yet be in a state of unity with the world of perception. When one is one with the world, one can either be mindful of the detail that is contained in that unity, or not; from the standpoint of oneness it does not matter. Too much mindfulness is unhealthy from a spiritual point of view and uneconomical in terms of our use of energy. To be natural, we must reach a balance between presence and absence. In Gurdjieff’s system, one cannot drop self-reference without losing self-awareness. Due to this requirement for continuous self-referral, one is bound to feel a sense of separation from the world of perception.

When it perceives the world from awareness, the observer is absorbed in the pure subjectivity of that awareness. The observer is arising from awareness in order to identify perceptual reality. Since awareness is not self-referencing, but remains still, resting in its subjectivity, it does not experience itself in contrast to the outer. To see the world from awareness is the first level of what in Buddhism is called ‘mirror-like consciousness’. While very positive, the realization of awareness also has its limitations. It is still too present and lacks the balancing aspect of surrender. Only from pure consciousness can we truly see things as they are, for our me is then absorbed in absence, the unmodified state of existence.

Seven Levels of Man

Gurdjieff spoke about seven stages in the evolution of man, or the seven levels of man. Man number one is the physical or instinctive man, for his body (the moving center) is his main center. Man number two is predominantly based in his emotional center and lives through his emotions. Man number three lives through the mind or mental center. These first three stages illustrate the imbalance in Gurdjieff’s mechanical man, where a single center dominates the others. Although the other centers are still present, they are very weak. These people are called ‘one-centered’ because they perceive reality through just one center. Man number four represents a stage in development where the three centers are more integrated; he is called ‘a balanced man’. Man number four is a transitory stage between the third and the fifth stages. It is from this level that one begins the Work and self-observation.

The descriptions of man number five are less clear and therefore open to various interpretations. He has established a permanent center of self-awareness and a crystallized I and has awakened his higher emotional center. In our terminology, we would say he has reached conscious me with the inclusion of the heart.

Interestingly, Gurdjieff says that one can become man number five through right work or through wrong work. If it is done wrongly, one reaches the fifth stage directly without passing through number four. But if one does so, one then has no chance of reaching stage number six, unless one’s crystallized essence is melted, which requires going through terrible suffering. This statement indicates that man number five, in this case, has not attained awareness, but rather has solidified his conscious me. Why? Because only by being linked to the heart (in the absence of I am) can conscious me be open enough energetically to evolve further into awareness. Without heart, conscious me is simply too crystallized and energetically locked in its own presence, which blocks its further evolution. To move directly from man number three to five means one’s mental center is overdeveloped relative to the other centers, and this prevents the awakening of conscious me in a way that it can be balanced or open enough for further evolution into awareness. Such a conscious me is bound to be overly identified with the observer.

Man number six and man number seven share the same level of attainment, but only number seven has attained a permanent state. Man number six can still lose his level and regress. It is said that man number seven attains the full potential of human development and has complete knowledge of all there is to know – a superman. Gurdjieff says man number seven has achieved a permanent I, individuality, complete free will, and immortality within the limits of our solar system. According to Ouspensky, men number six and seven have achieved the realization of objective consciousness, which would include what Gurdjieff called ‘the higher intellectual center’. We can conclude this to mean that men number six and seven at least reach awareness, but possibly even pure consciousness.

It is interesting to compare Gurdjieff’s term ‘objective consciousness’ with the term ‘pure subjectivity’. There is no conflict between these words, even though, on the surface, they seem to mean the opposite. Gurdjieff used the term ‘objective’ not to mean ‘external’ but to denote that it is beyond any influences of the relative me. It is objective because it is independent of me. So it could be also called ‘objective subjectivity’. The term ‘objective’ makes it feel more impersonal, and could also reveal a certain lack of integration between the energetically realized pure subjectivity and me as the one who embodies it. If me does not reach unity with the space of pure subjectivity, this subjectivity is being translated in our intelligence as objective. That’s why in Buddhism, as well as in other paths, it is common to translate realization of our pure nature as emptiness or awareness that ‘no one’ is experiencing.

It seems to make more sense for there to be eight levels of man in total, and to add one in-between man number five and man number six. It is unlikely that the realization that follows man number five yields a constant experience – that man can still lose his state. Gurdjieff was after all attached to the concept of ‘the law of seven’ (a number which in many esoteric circles is considered sacred), and perhaps this is why he did not describe this intermittent stage.

Gurdjieff’s Own Misperception of Attention

The first half continues all the time uninterruptedly to watch, with so to say ‘concentrated interest,’ the result proceeding from the process of my breathing. I now consciously direct this second half of my attention and, uninterruptedly ‘remembering the whole of myself,’ I aid this something arising in my head brain to flow directly into my solar plexus. I feel how it flows. I no longer notice any automatic associations proceeding in me. In spite of the fact that I have done this exercise just now among you for the purpose of illustratively elucidating its details to you, I now begin at the present moment to feel incomparably better than before beginning this demonstrational explanation.

— Life is Real Only Then, When “I Am”

Paradoxically, in spite of attention being the heart of self-awareness and the essence of Gurdjieff’s work, he did not seem to identify precisely enough either bare attention (attention in and of itself) or the source of attention, which is conscious me. He also did not seem to be fully clear what “something arising in my head brain” actually is. In addition, he mixes up the attention of the observer with psychosomatic attention that, in this case, brings the feeling of breath and the body into focus. Here, attention is not aware of attention, but rather is in a subject-object relationship with other aspects of our internal reality. Why did he feel better by becoming aware of his solar plexus, while using the two halves of his attention as described? This is because by directing what may be vertical surrender of this ‘head-brain something’ to his belly, in conjunction with breathing, some energy dropped into being, creating certain relief from the otherwise constant observation.

As surprising as it may sound, Gurdjieff’s techniques, such as his special dances or movements, are actually the wrong practices for awakening the correct attention. He proposes practices in which one pays attention to three centers at the same time: the physical, the emotional (solar plexus), and the mental. However, because our attention has limited power, it has to exert itself beyond its natural capacity by using an excessive amount of will to maintain focus on all those centers, which results in the over-crystallization of one’s willpower. The evolution of consciousness is not about achieving supernatural attention, but rather awakening its subjective dimension. Gurdjieff did not seem to recognize that it is unnatural and harmful for our attention to be focused on so many aspects simultaneously, for it is simply not meant to contain such a broad field of perception or experience.

Gurdjieff was not conceptually aware of the important difference between the external attention of the observer and the pure attention of conscious me. Pure attention does not ‘pay attention’, but rather merges into unity with the centers of I am (consciousness, heart, and being). Pure attention can merge with the heart and being by embodying I am and giving birth to pure me, but it cannot merge with the solar plexus (until a very advanced stage of practice in which pure me of the heart expands into it) because the solar plexus is not a center of I am. Only from pure attention and pure me can we encompass all the aspects of our identity without conflict and effort. The attention Gurdjieff was activating was not pure attention, but rather the external attention of the observer, which is not linked directly to the soul and I am.

While embracing our whole body in consciousness is positive, this is not done by the forceful expansion of attention, but rather by vertical evolution and surrender. Those whose practice it is to pay total attention to all the three centers, and to additionally keep ‘watching’ (the first level of attention linked to intelligence), are going completely the wrong direction – they are turning themselves into a new type of man-machine, a super-attentive robot. Similarly, to develop the habit of excessive self-observation can easily make one overly mental. People are already too mental, so why exacerbate this further? When this self-observation is then linked to excessive attention, one can cut oneself off from the soul. Following the path of Gurdjieff in this way can be a double-edged sword, for one might easily move from being a man-machine to being a superman-machine instead. It is the kind of improvement that borders on retrogression. Too much attention and too much self-observation will block both awakening to pure subjectivity and surrendering to the soul.

The Need for Someone Who Knows

A man can only attain knowledge with the help of those who possess it. This must be understood from the very beginning. One must learn from him who knows. . . . . . . The moment when the man who is looking for the way meets a man who knows the way is called the first threshold or the first step. From this first threshold the stairway begins. Between ‘life’ and the ‘way’ lies the ‘stairway.’ Only by passing along this ‘stairway’ can a man enter the ‘way.’ In addition, the man ascends this stairway with the help of the man who is his guide; he cannot go up the stairway by himself. The way begins only where the stairway ends, that is, after the last threshold on the stairway, on a level much higher than the ordinary level of life.

— In Search of the Miraculous

Many of Gurdjieff’s ideas were developed further by his close disciples, who might have not realized the essence of his teaching deeply enough. There were many conflicts between Gurdjieff and his students, as he liked to challenge them in all kinds of ways, and required of them an unquestioning obedience. Gurdjieff himself had a very obscure style of writing, as if purposely making his books convoluted and hard to decipher. He became known and popularized mainly through the books of P.D. Ouspensky, a man of high intellect who chose to separate from Gurdijeff and open his own school. He was under the illusion that he could keep evolving just by following the system, in separation from the teacher who was the living source of that system, although he did commission one of his leading students to find the source of Gurdjieff’s teaching.

Even though the essence of his teaching was the inner work, Gurdjieff saw the role of the master as crucial in reaching higher states of consciousness. Up to the stage of man number four, one can evolve by oneself, but to go any further one needs help. For instance, man number four needs help from man number five, and man number five needs help from man number six or seven. One of the main reasons Ouspensky left Gurdjieff, other than having various judgments about him, was that he did not like the idea of being dependent on another human being. He thought that the system and the Work alone could take one where one needs to go. In reality, however, those who do the Gurdjieff Work without the grace of the master can only achieve very limited results. Ouspensky himself had to pay the price for his pride – stagnation in his development. After Ouspensky’s death in 1947, his wife advised both his and her students to go to Gurdjieff in Paris.

As Gurdjieff himself said:

No work of groups is possible without a teacher. The work of groups with a wrong teacher can produce only negative results.

— In Search of the Miraculous

The Pitfalls of Gurdjieff’s Work

It is challenging to define Gurdjieff’s teaching as it includes so many elements. For instance, his vision also embraced the need for emotional transformation. He spoke of the lower and the higher emotional centers (the solar plexus and the heart) and the need to transform the lower center through embodying the qualities of the higher emotional center. He identified fear and violence as the most negative emotions, both being negative reactions to the challenge of survival. One of the purposes of the fourth way was to develop and integrate the so-called three centers: intellectual, emotional, and physical. This was part of his vision of a complete and harmonious man.

As a general observation of Gurdjieff groups active today, their practices seem to be very mind-oriented and tend to over-crystallize the observer. We cannot consider such a path, as it now appears to be, a balanced one. An excess of self-observation locks people even more into their mental selves and makes them even more lost. Although self-awareness needs to be developed to some extent, its overdevelopment is harmful. It is very difficult to get rid of an overly solidified observer as it not only blocks our surrender to pure consciousness, but can also even prevent the awakening of both awareness and conscious me. Having a weak observer is a big problem, but having a monstrous one is even worse. This would, perhaps, be the greatest danger and probable pitfall in following the teachings of Gurdjieff, or at least the most commonly accepted views of it. Some of the Buddhist traditions suffer from the same problem: too much attention and too much mindfulness – too little ease, too little relaxation, and too little surrender and absence. As the human mind is already separated from the whole, excessive attention will result in even more separation.

In our teaching, self-remembrance refers to a very different practice and realization, because we add the dimension of I am – that which is beyond me. It is not the observer who maintains and cultivates the state of I am. The observer is neither remembering nor being remembered. We are remembering I am from pure me and pure me from pure attention, which flows into I am from conscious me. Here, the observer is entirely by-passed as we evolve into the deeper dimensions of our pure subjectivity.

Revolutionary but Incomplete Teaching

One of the elements that is missing in Gurdjieff’s teaching is that of the vertical evolution into being. He did use the term ‘being’, but to point to our solid existence or presence beyond the mind, or the real I. True being points to vertical absorption in the source. Gurdjieff’s is not the path of being, although a limited connection to being could be developed based on his emphasis on the work with the moving and feeling centers. His is primarily a path of awareness that also includes many elements of psychological work.

There were also many esoteric aspects to his teaching, some of them rather strange and even extravagant. He had a creative mind and liked to keep exploring reality from different angles. He spent much of his energy developing a sort of pseudo-scientific esoteric system of reality. His system is not dissimilar to European occultism or the Jewish Kabbalah, the latter being a rather hopeless attempt to construct a spiritual vision of reality based on linear mathematical or geometrical laws. Because of his fascination with hypnosis, telepathy, the paranormal, and all kinds of ways of manipulating psychic or material reality, he could also be accused of spiritual materialism, or of being over-distracted by inessentials. Aside from extreme intellects, most people who wish to study Gurdjieff are not interested in his cosmology or convoluted explanations of the various laws of the universe. For them, studying such obtuse matters just adds further burdens for their minds to carry. Seekers enter the path because what they most want is to find release from suffering and some semblance of peace – and rightly so.

To avoid answering useless metaphysical questions, Buddha told the following parable. Suppose a man is struck by a poisoned arrow and the doctor wishes to take the arrow out immediately. Suppose the man does not want the arrow removed until he knows who shot it, why it was shot, and the age and parents of the person who shot it. What would happen? If he were to wait until all these questions have been answered, the man might die first.

It seems that, in his preoccupation with unraveling the various laws governing this universe, Gurdjieff got sidetracked from going deeper into the science of self-realization.

Gurdjieff’s explorations of the inner world of the self were far from complete. And even if he felt complete inside, his teaching lacked many important aspects and clarifications of the spiritual process. It is no wonder many of his concepts are open to various interpretations and tend to confuse his followers. It would have been a great help for posterity if Gurdjieff had put more effort into explaining the fundamental concepts of his teachings in more detail, such as what the real meanings of self-awareness and objective consciousness are, or elaborating more clearly the state of man number five. He seemed at times to have forgotten what really matters.

The Absence of Sudden Awakening

The over-gradual nature of Gurdjieff’s path can also be considered a flaw. Any higher path must be rooted in the principle of sudden awakening. His system is too gradual, too slow – working, working, working – so much so it feels painful. There is, of course, a place for work and gradual progress on the path, but not when it is too linear. Where is the magic of the sudden realization of our pure nature, of meeting our essential self, and of opening the portal to I am? On the path to awakening, there are often shortcuts, sudden leaps, and shifts. When one enters the state of pure subjectivity, the practice ceases being one of only hard work and becomes sheer pleasure. One stops self-observing like an automaton and experiences more of the moment to moment return to the bliss of the higher self. Self-remembrance then becomes a movement of love, rooted in surrender and merging with the beyond.

Where Gurdjieff’s teaching appears to come to an end conceptually, the true evolution into our soul and samadhi into the beyond is actually just beginning. Our development on the level of me is extremely important, but unless we create a conscious link of surrender with universal subjectivity, we are bound to find ourselves in utter stagnation and despair. The path Gurdjieff created was primarily a path of will, concentration, and knowledge – not of surrender. There was very little sitting meditation, other than what he called ‘morning preparation’, which involved more of a mental contemplation than diving into ‘just being’. As much as active meditations are great tools in awakening of consciousness, without going through the training of sitting meditation, one has little chance of awakening the vertical dimension of consciousness and deeper states of samadhi.

On some level, Gurdjieff’s teaching can be seen as a kind of meeting between western esoteric traditions and eastern mysticism, a combination that did not work perfectly well because the excessive mental energy of western occultism, together with the exploration of the esoteric, were simply too crude to match the depth of the eastern spirit of enlightenment. Even though Gurdjieff drew many of his discoveries from Sufism, he took their knowledge out of the context of their path of love and devotion, which otherwise serves as an existential balance to the path of knowledge and awareness. It is no surprise that the path he created became overly mental.

Gurdjieff – A Merciless and Compassionate Pioneer

In spite of the limitations of his approach, we should not forget how great Gurdjieff’s impact on western spirituality was in times when people were so much less in touch with the longing to find their true self and to awaken. The concept of finding our real I was almost completely absent in western culture at that time. People were interested in esotericism, not in self-realization: nobody even had the concept that they were not self-realized. For instance, the Theosophical Movement, co-founded by Helena Blavatsky, collected all kinds of scriptures from the East, and mixed that knowledge with theories from their psychic visionaries, but the product was effectively just esoteric mental knowledge. In contrast, not only did Gurdjieff realize his essence, but he also created a unique and revolutionary system of inner work, that could be integrated with everyday life, to facilitate realization of that essence.

His approach to human development was very holistic, including body, mind, emotions, and consciousness. He was one of the rare teachers to create a vision of wholeness that aims at the actualization of a complete human. Above all, he will always be remembered as the man who, with great power of insight and absolute conviction, challenged the collective state of spiritual amnesia. With his merciless compassion he revealed to humanity the cruel truth that everyone is asleep. Gurdjieff was a true pioneer and a man of truth. Of how many people on this planet can this be said?

Blessings, Aadi

For a definition of the terminology used, please visit the Glossary page. Click here for a printable version of this article.